Victoria’s MMC Statement is a meaningful step. It positions MMC as a practical lever for Australia’s housing challenge: faster delivery, higher quality, stronger cost certainty, and lower carbon. It also signals intent across regulation, approvals, skills and government procurement.

But if the goal is scale, the Statement still reads more like a “policy toolkit” than a repeatable operating model. Some pilots struggle to replicate and spread—not because the methods themselves have failed, but because the supporting compliance pathways, delivery mechanisms, and verifiable evidence remain highly project-specific. Transaction costs stay high, lessons don’t compound, and the sector struggles to enter a self-reinforcing cycle of iteration.

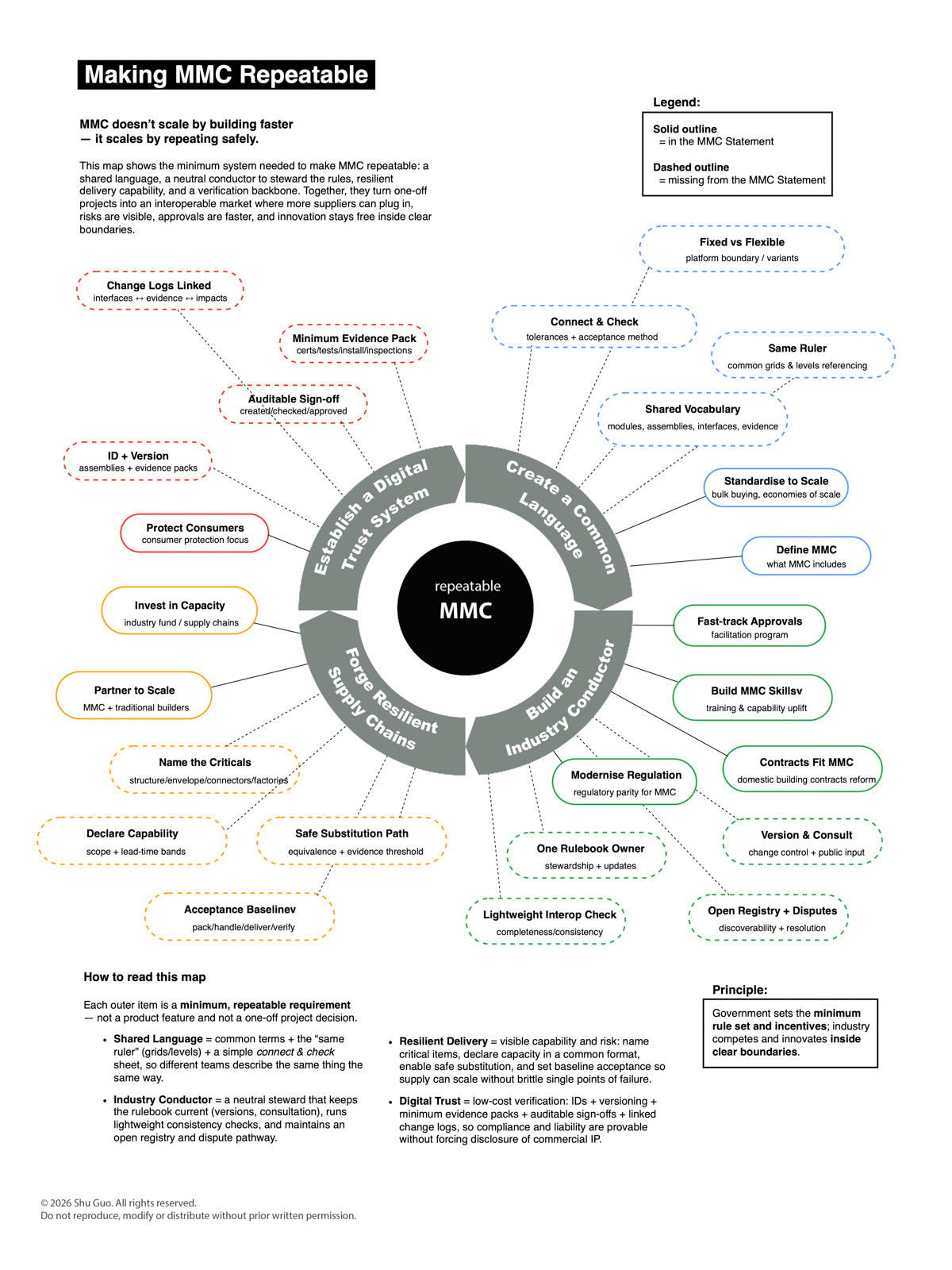

The analysis below offers an ideal blueprint: it outlines the essential system building blocks required for MMC to scale and the logic that ties them together. It does not assume they can be implemented simultaneously or delivered in one step.

Across typologies—modular, panelised and, in specialised contexts, additive manufacturing—the requirements for scale are consistent: a shared rules language and verifiable delivery mechanisms.

The discussion therefore centres on three system-level gaps: common rules, repeatable delivery, and verifiable trust. To prevent these settings from resetting on every project, a neutral stewardship function is also required—so the “rules of repeatability” can be versioned, maintained, and reused.

First, credit where it’s due: what the Statement gets right

The Statement covers several important policy levers, including: a push toward regulatory parity; an intent to accelerate approvals; a direction of travel on contract and progress payment settings that better reflect factory-frontloaded value; and capability signals through skills and government procurement. It also gestures toward improving industry capability visibility and matchmaking. These are solid foundations.

The issue is not direction. The issue is that to turn direction into repeatable capability, several institutional mechanisms still need to be specified.

What’s missing: three system building blocks that make MMC repeatable

1) A common rules language: interfaces, tolerances, proportional logic

MMC is often framed—understandably—through the lens of “off-site manufacture” and factory output. That framing matters, but it can also keep the conversation trapped at the level of delivery form and capacity. The real determinant of whether MMC can scale is usually a higher-order system capability: a rules language that is typology-agnostic (interfaces, modular coordination, tolerances and proportional logic), and the repeatable compliance and delivery mechanisms that sit on top of that language.

Without this layer, MMC remains project-by-project customisation rather than industry-level capability. In practice, projects may also end up compromising on avoidable constraints—such as ceiling heights or service zones—simply to fit the limits of a given system, rather than because those outcomes are intrinsically necessary.

For example, many residential systems still default to 450mm stud spacing, a legacy shaped by historical plaster/render considerations and site labour efficiency. In contemporary modular and panelised delivery, we should be far more deliberate: cladding and lining sheet sizes, shipping constraints, and even common lot-, especially small lot-, widths should inform modular coordination and interface rules. Otherwise, “standardisation” rarely translates into cross-project repeatable efficiency.

2) Repeatable delivery mechanisms: DfMA templates and responsibility boundaries

Even with mature technical systems, MMC can fail to scale when delivery responsibilities are unclear. What’s missing is not another layer of rhetoric, but a delivery mechanism that can become the industry default—and that can be anchored to procurement and acceptance. In practical terms: a DfMA deliverables set, defined hold points, and a clear RACI that draws the responsibility boundaries (who designs, manufactures, transports, installs, commissions, and signs off).

This is often seen as “industry work”, and it is. But government can materially accelerate convergence by making these elements default in public procurement templates; by institutionalising what factory-based evidence is acceptable for compliance and acceptance; and by standardising handover and sign-off protocols so risk boundaries are clear and repeatable rather than re-negotiated on every project.

In system terms, this is also where delivery “resilience” begins: not as a geography story, but as supplier architecture and repeatable capacity—clear capability declarations, bottleneck visibility, and safe substitution pathways that preserve compliance and quality without resetting the project.

3) Verifiable trust infrastructure: traceability, third-party certification, and bankability

In MMC scale-up, trust is a form of currency. Without verifiable evidence, regulators tend to fall back to conservative inspection models; insurers price uncertainty into premiums; financiers tighten terms. The outcome is slower approvals and higher costs—precisely the opposite of what MMC is supposed to achieve.

For example, today’s trust mechanisms often swing between CodeMark and case-by-case determinations by surveyors or engineers. Both are expensive in different ways: CodeMark is time- and resource-intensive and cannot practically cover the full diversity of materials and systems; case-by-case determinations are difficult to replicate and subject to human variability. Add the reality that the “same” material can be registered under different entities and become non-interoperable, and the system produces repeated certification and repeated proof—creating friction and barriers rather than scalable confidence.

A modern trust infrastructure has at least three parts: a component/system-level digital passport (unique ID, performance declarations, test records, audit links, installation and handover records); a third-party certification and audit pathway aligned with regulatory acceptance so evidence can travel and be reused; and a mechanism that converts trusted evidence into market outcomes—insurability, clearer warranty responsibility, and finance access (including green finance).

The stewardship function that stops the system resetting

The three blocks above do not close by goodwill alone. To become reusable across projects, they need a neutral stewardship function—an “industry conductor”—that keeps the shared settings current and usable.

In practical terms, this stewardship function would maintain the conventions and templates that underpin repeatability: publish versions, run a clear change process with targeted consultation, maintain a registry of declared systems and evidence, enable lightweight interoperability checks (completeness and consistency, not heavy re-certification), and provide a dispute pathway that reduces repeated negotiation and ambiguity in liability boundaries.

This is not about centralising the industry or picking winners. It is about making the minimum shared settings stable enough to reuse and light enough to adopt—so firms can compete and innovate inside clear boundaries.

Why these gaps matter

The levers Victoria has highlighted—regulatory parity, approvals acceleration, procurement and skills—are necessary conditions. But they do not automatically produce scale. Scale is fundamentally about repeatability. Repeatability requires institutional building blocks that reduce transaction cost, reduce risk premiums, make compliance predictable, and allow industry learning to accumulate rather than reset on every project.

For example, NCC and AS 3740 diverge in certain details (such as interpretations around water stops), and projects are often pushed into performance solutions on a case-by-case basis—time-consuming, resource-intensive, and inconsistent. If MMC had a clearer, verifiable, and reusable “high-standard” approach in these areas—tied to factory-controllable evidence—approvals acceleration becomes closer to a system outcome, rather than a marginal policy preference.

If Victoria closes these gaps, MMC can move from isolated demonstrations to an operating model that learns and improves over time: less approvals friction, better cost certainty, fewer defects, lower embodied carbon—and, critically, more rational risk pricing from insurers and financiers.

A brief note on overseas supply chains

This piece does not expand on overseas supply chains as a complementary pathway—not because the potential isn’t real, but because the topic depends on more fundamental system capabilities: a common rules language, repeatable compliance and delivery mechanisms, and verifiable trust infrastructure.

Here, “resilient supply chains” refers first to repeatable delivery capacity (supplier architecture, bottleneck/SPOF visibility, substitution pathways, and acceptance baselines), not a standalone discussion of offshore supply. Without these foundations, cross-border capacity simply amplifies the same problem—from project-specific proof to cross-border project-specific proof.

In later research, once the “system bottom” is clearer, I will address how Asia–Pacific supply chains can become a constructive supplement through a closed loop of certification, traceability, insurance and finance.

Victoria’s Statement has set direction. The next step is to specify—and then progressively build—the system building blocks that turn direction into repeatable capability, so MMC can genuinely scale.