When we talk about prefab housing, a common fear arises:

“Won’t standardisation make everything look the same?”

This fear confuses standardisation with sameness. A well-designed system doesn’t constrain creativity – it can actually liberate it.

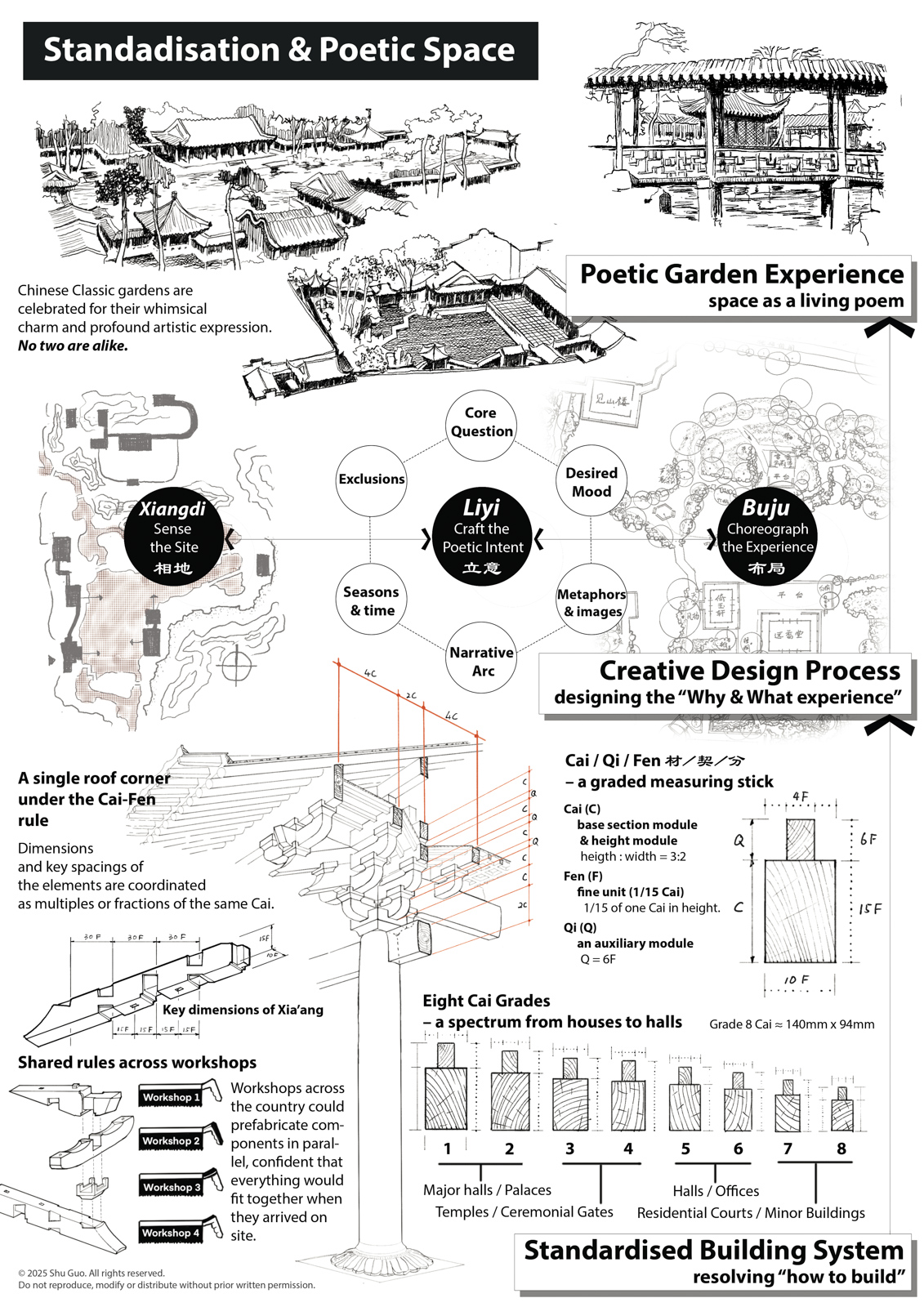

Consider the classical Chinese garden: a world of whimsical charm and deep artistry, where no two gardens are alike. Far more than a mere outdoor space, it was a personal universe: a library for the scholar, a studio for the artist, a quiet retreat for meditation, and a gracious setting for hosting friends, enjoying music, and staging opera. Most importantly, it was a world in miniature, crafted by its owner to be a spiritual haven. In essence, designing such a garden was akin to designing a complete, contemporary dream house.

Surprisingly, many large, complex gardens were built in just two or three years, while comparable Western or West Asian estates often took a decade or more. This speed is striking when you realise how dense these gardens are with architecture – halls, pavilions, bridges, roofed walkways, and more.

How did designers and builders achieve both creativity and speed centuries ago?

The system underneath the poetry

The key was a systematic, modular approach to building. All these structures shared a technical root: the cai-fen system.

The cai-fen system provided the essential modular language: instead of fixing components with one-off dimensions, it expressed them through proportional relationships. At the heart of this language was a base unit, cai – a standard timber section and height module – defined in eight graded sizes for different building scales, from small houses to major halls. Once the appropriate cai grade was chosen for a project, it set the base size for the whole building; beams, columns, brackets and key spacings could then be derived as multiples or fractions of that unit. Because every workshop was working from this same graded modular language, they could prefabricate parts in parallel, confident they would fit together on site.

Yingzao Fashi (the 1103 “Treatise on Architectural Methods”) turned this language into a complete architectural operating system. It integrated what we would now call building codes, material standards and design patterns – all expressed in the consistent, proportional units of the cai-fen system. Because it was issued as an official state manual, it functioned as a national reference: court architects, local officials and workshops could all work from the same script for how buildings should be conceived, costed and assembled, while composition and intent remained free to vary from place to place.

In short, a national construction system, reinforced by centuries of craft practice, had already resolved most of the “how”: structural logic, connections, sequences of work, material handling and much of the overlap between design, engineering and site management. The heavy technical thinking was pushed down into standards and into the hands of experienced craftsmen.

As a result, the designer’s mind was freed to focus on the highest level of creation: the experience. They could pour their energy into:

XIANGDI – Read and Sense the site

With the “how” resolved by the system, design begins not with technical constraints, but with a deep, almost poetic, reading of the land. Xiangdi means to sense the character of a place: its topography and water flow, the borrowed scenery of distant mountains, the path of the sun and wind, and the subtle indications of the site’s past and potential. It is an act of listening before drawing.

LIYI – Craft the Poetic Intent

Liyi is where the soul of the garden is defined. It answers the core question: “What should this place mean?” It establishes the desired mood—serenity, exhilaration, contemplation—and chooses its governing metaphors and images: is it a mountain retreat, a waterside labyrinth, or a scholar’s microcosm? It sketches the narrative arc of a visit and considers how light, shadow, and the seasons will animate the space. Crucially, it also decides what must be excluded. Liyi does not draw a single line; it sets the poetic and conceptual boundaries within which all physical form must resonate.

BUJU – Choreograph the Experience

Buju is the composition of the spatial poem. With the intent set, it arranges all physical elements—paths, walls, openings, water, rock—to choreograph the embodied experience. It dictates the rhythm of movement and pause, controls the sequence of views through concealment and reveal, and calibrates dimensions and enclosure to shape the emotional cadence of the journey. The result is not a circulation diagram, but a carefully scored sequence of compression and release, intimacy and expanse.

The diagram below is a three-layer sketch of that relationship:

The system carries the “how” at the base, so that design intent and lived experience can range more freely in the “why” above.

Same components. Same rules. Completely different poems.

Standardisation here is not a reluctant compromise that creativity merely “coexists” with. It is what liberates creativity – by carrying so much of the load of the “how” that the “why” can be pursued with focus and courage.

The core lesson

The real question is not “does standardisation kill creativity?” but “is our standardisation wise enough to cultivate it?”

A clumsy system breeds repetition. An elegant system cultivates expression.

The classical Chinese garden shows that efficiency and poetry can share a common root. When a deep system carries the “how”, the poetry of the “why” can be freely composed.

For a longer essay that expands this line of thinking into Australia’s housing crisis and MMC reform, I’ve written “An Ancient Fix for Australia’s Modern Housing Crisis: Rethinking MMC” – available on shuguo.archi.

Independent research – views entirely my own.